The Eddy Line

THE WET PLANET BLOG

Many people think the whitewater season begins in the heat of summer, but prime time for rafting and kayaking...

Read More

March 2025 | Aleson Rietow

At Wet Planet, our guides don’t just hang up their paddles when the season ends. While some of our...

Read More

March 2025 | Aleson Rietow

Are you are planning to get out on the river with Wet Planet in April or May to raft,...

Read More

February 2025 | Aleson Rietow

The lazy days of summer are fast approaching (yes, even in winter, it’s never too early to dream), and...

Read More

January 2025 | Aleson Rietow

Looking for a unique and unforgettable wedding group activity? Whether you’re planning an adventurous bachelor or bachelorette party or...

Read More

January 2025 | Aleson Rietow

It is never too early (or too late) to start a new hobby. So why not begin your journey...

Read More

December 2024 | Madalyne Staab

Written by Leah Collins There’s really no feeling like when you set out on the raft into the gorgeous...

Read More

December 2024 | Aleson Rietow

By Lisa Conway Not long after the inception of the Wet Planet Kayak School in 2004, professional kayaker and...

Read More

December 2024 | Aleson Rietow

What we are grateful for? So many things, as we, each day feel fortunate to do what we do...

Read More

November 2024 | Madalyne Staab

Halloween is just around the bend, and if you’re anything like us, you’re probably looking for a costume that...

Read More

October 2024 | Aleson Rietow

While the end of the season is always bittersweet – tears were definitely shed as members of our team...

Read More

October 2024 | Madalyne Staab

September in the Columbia River Gorge is best described as all the fun with none of the summer crowds....

Read More

August 2024 | Aleson Rietow

Have you ever seen people winding down rivers or sliding through rapids in kayaks and wondered “How does someone...

Read More

August 2024 | Aleson Rietow

Please allow us to preface; celebrating the women of Wet Planet does not discount or take away from the...

Read More

July 2024 | Aleson Rietow

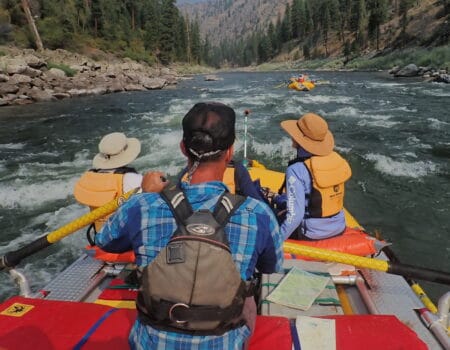

Embarking on a multi-day whitewater rafting adventure on the Main Salmon River provides an exciting opportunity to experience nature...

Read More

June 2024 | Aleson Rietow

Thanks to being surrounded by so many amazing rivers – from relaxing Class I all the way up to...

Read More

June 2024 | Madalyne Staab

While the main volume of trips Wet Planet runs are on the White Salmon River in Washington, we also...

Read More

June 2024 | Madalyne Staab

I don’t know about you, but my mama has always been, and still is, my biggest inspiration for my...

Read More

May 2024 | Aleson Rietow

Alex Taylor, joined the the Wet Planet Team in 2021. In the 2 years since we have come to...

Read More

March 2024 | Steve Merrow

With a fresh four feet of snow piling up high and the rafting season a month away, it’s a...

Read More

March 2024 | Steve Merrow

At Wet Planet, our love for adventure is rivaled only by our dedication to preserving the natural world that...

Read More

March 2024 | Kali Bennett

Any river lover remembers the magic of that first whitewater rafting trip well. We remember the anticipation, excitement, and...

Read More

February 2024 | Aleson Rietow

It was not hard for the Wet Planet spotlight to find Marcus Tarzian. Marcus quietly has made himself one...

Read More

February 2024 | Aleson Rietow

Intrigued by the idea of a multi-day river trip in Idaho or Oregon, that includes the remote and peaceful...

Read More

January 2024 | Aleson Rietow

Top