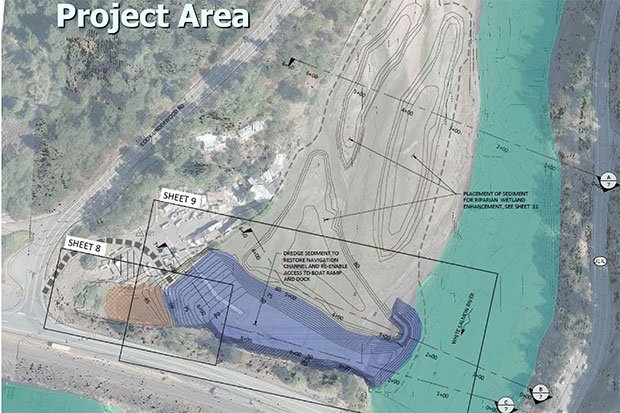

An aerial shot of the nearly completed construction at the Underwood in-lieu site. Photo provided by Yakama Nation Fisheries

This winter the redistribution of sediment, creation of new waterways, and a bright cofferdam floating in the mouth of the White Salmon River has received much attention from the community. The restoration project at the in-lieu site located at the Underwood side of the mouth of the White Salmon River has, while interesting to watch, also spawned curiosity about what “in-lieu sites” are and why they’re important. As we look for answers, a story behind the development of the Pacific Northwest emerges, explaining how all that sediment came to settle in the navigation channel at in-lieu site. We also explore what in-lieu sites are and what their tie to salmon is, and the connection between the cultural heritage and significance of salmon with the development of the Columbia River, its dams and the indigenous tribes.

Where did that dam wall come from? – A brief history of salmon and development in the PNW

Why all this effort for fishing access and salmon habitat? Many cultures or regions have an icon, and here in the PNW, we find ours in the salmon. The area is not only renowned for our salmon runs, but salmon swim through the region’s history and help to shape its future.

At the time of the Oregon Trail and migration west, the native tribes of the PNW were considered some of the richest in the nation due to the bounty of salmon that fed the people and their culture and allowed brisk trade with tribes from other regions. The tribes believe that salmon give their lives to sustain tribal people, so it is their responsibility, in turn, to take care of the salmon. The life cycle of the salmon, fed in the beginning phases of their life by these pristine tributaries, then fed the same land and waters in their death as they brought nutrients from the Pacific Ocean back upstream. This cycle is a great part of the reason that the PNW harbors some of the most diverse ecosystems in the world, a harmonious balance that was realized a bit too late as the west became more civilized.

By the first half of the 1900s, much of the PNW had been dammed, including the White Salmon River with the Condit Dam, and more notably, the Columbia River – the largest watershed in the Northwest spanning 5 states and 2 Canadian provinces. Damming the Columbia and its tributaries turned a once lively ecosystem into a series of controlled pools. While the advancement of hydroelectricity via dams was an incredible technological accomplishment, it compromised thriving ecosystems and placed huge barriers in the way of the annual returns of 10-16 million Chinook, Coho, Steelhead, Chum, and Sockeye salmon, along with a number of other migratory fish like the Pacific Lamprey, Smelt, Sturgeon, and more.

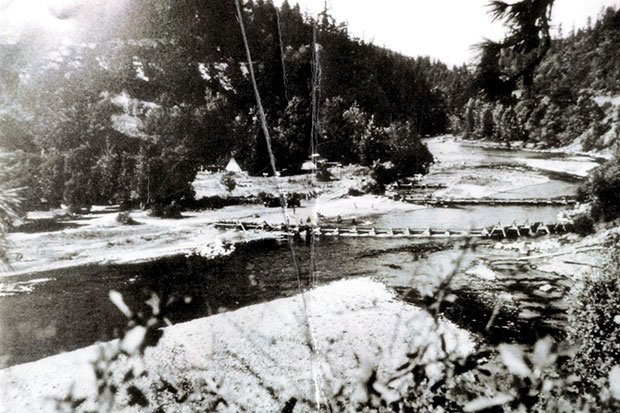

US Bureau of Fisheries weir in the early 1900s with Underwood (namnit) village in background, where fall chinook salmon brood were captured for Spring Creek national fish hatchery.

What are In-Lieu sites?

Many native tribes of the area whose livelihoods had been sustained by salmon for millennia, found that their homes, fishing sites, and other areas of importance would be inundated in efforts to harness the power of the Columbia River. As a part of the 1945 Federal legislation (Public Law 79-14) in-lieu sites were established along the banks of the river in the decades following construction of the dams to help replace fishing sites for the Columbia River treaty tribes. One of the first in-lieu sites was built at the site of the Namnit Indian village (the Underwood in-lieu site,) which had been at the mouth of the White Salmon River for centuries.

Saving the Salmon

Between the years of 1997 and 2004, many species of salmon in the Columbia River were listed under the Endangered Species Act, with Fall Chinook and Coho at the risk of extinction by 2004. The Condit Dam on the White Salmon River, built in 1911, blocked access to 33 miles of steelhead habitat and 14 miles of salmon habitat. It was removed in 2012 in hopes to help restore the salmon runs on the White Salmon River.

With the removal of Condit Dam, salmon regained access to miles of habitat upstream on the White Salmon River and its many tributaries. At the same time, kayakers, rafters, and anglers alike now have the ability to float a free-flowing river all the way to its confluence with the great Columbia River. The deconstruction of Condit Dam(the largest dam to be removed in the U.S. at its time), and subsequently its reservoir, once called Northwestern Lake, has resulted in enormous changes to the White Salmon River watershed, riverbanks, and salmon runs.

Unleashing the lake bed

One of those changes was a great amount of the sediment that had built up in Northwestern Lake was pushed downstream. As was to be expected, the Underwood in-lieu site, located at the confluence of the White Salmon River and Columbia River, had its dock and river access blocked as a result of this sediment release. As this was an anticipated result of the dam removal, the Condit Hydroelectric Project Settlement Agreement was formed in 1999 with PacifiCorp Energy, setting aside funds to aid the Bureau of Indian Affairs in this restoration project.

What’s going on at the Underwood in-lieu site?

Bill Sharp, project manager and fisheries research scientist for the Yakama Nation, explains why the project is happening now. “We wanted to wait a few years to watch that gravel bar settle. We looked at how it reacts to flow events and pool elevations, and we feel like it’s in a stable enough condition to do this work.”

The restoration project, spearheaded by Yakama Nation Fisheries Program, designed by InterFluve, Inc. of Hood River, and executed by Tapani, Inc. of Battle Ground, is a multiple-phase project. First, the navigation channel, which allows tribal fishers boat access to Columbia River fisheries, was excavated to around 7 feet in depth. The excavated sediment was then used to build a series of side channels and small riparian islands, which have been replanted with native plants this spring.

The project is currently in its revegetation phase. We should see lots of native plants growing throughout the summer. Photo provided by Yakama Nation Fisheries

Lower elevation channels in between the islands were left to provide habitat for juvenile salmonids when Columbia River levels between The Dalles Dam and Bonneville Dam, referred to as the “Bonneville Pool”, are raised and lowered for power production, flood control and navigation by the Army Corps of Engineers. The goals here, beyond enhancing the navigation channel and restoring fishing access to the Columbia River from the Underwood in-lieu site, are to reduce future sediment build up in the navigation channel, minimize shallow-water habitat to prevent the stranding of juvenile salmonids, and to restore native riparian plant communities. While this project is fascinating, if you’re tempted to check it out, please do so from afar. The new islands are part of the in-lieu site (tribal access only) and the restoration should not be disturbed to allow the new plantings to succeed.

How can I help the White Salmon River?

If you’ve been curious about the happenings of the Underwood restoration project, there are always opportunities to make your own contributions to helping maintain and protect salmon habitats on local waterways. Look for volunteer opportunities with local river conservancy organizations, such as SHARE the White Salmon River and Friends of the White Salmon River. You can also participate in this year’s annual White Salmon River Fest and Symposium to learn more and join in recognizing and celebrating the river and the life that surrounds it.

Full-Day rafting trips with Wet Planet floats through the old Northwestern Lake lake bed and canyons, the Condit Dam site, areas downstream impacted by dam removal, all the way down to the mouth of the White Salmon River at the Columbia River, where the in-lieu site is located.

For more information, please visit sources for this article at:

Underwood Uncovered: White Salmon River Restoration Project Underway by Enviro Gorge

The White Salmon River – A Free Flowing River on the Path to Recovery by Brendan Wells

The Meaning of Salmon in the Northwest: A Historical, Scientific and Sociological Study by Luisa Molinero

The Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

Additional sources and information provided by:

Mid-C Steelhead Recovery Plan, ICTRT 2006; McElhany et al. 2004

The invaluable insight and knowledge from Jeanette Burkhardt, Bill Sharp, and David Lindley with Yakama Nation Fisheries

Author Courtney Zink loves all things involving the river, and is always looking for new ways to explore them and share them with others. You can often find her guiding for Wet Planet, helping coordinate the annual White Salmon River Fest, or in the case that you can’t find her, meandering around in the woods.